From the bird’s nest to Borneo

As researchers, we often rely on interviews, surveys, and datasets to understand people’s needs. But what happens when we shift our attention to what’s not said – the way someone sits, the political logo on their t-shirt, or the quiet corner of a home that says more than words?

As a young bird still in her flight school years, I got the chance to explore this question by connecting my academic fieldwork with my internship at IS IT A BIRD. In February, I joined a group of interdisciplinary students from the University of Copenhagen and UNIMAS Malaysia to conduct fieldwork on sustainable rural livelihoods in a remote Bornean village. While others came from backgrounds in biotechnology, nutrition, and tourism, I was the lone anthropologist - and the only social scientist - in the group.

While others collected soil samples and mapped biodiversity loss, I focused on the messy, in-between layers: local politics, decision-making power, and unspoken social cues. I also brought along my camera.

Photography as ethnographic translation

Explaining what anthropology – and what in the world ethnographic research was – often had me repeating: “nope, no bones, it’s not archaeology, and yes, it’s more than just getting pissed off rice wine with locals”. Gradually, in between collecting soil samples from oil palm plantations and counting herbaceous species in the rainforest, I suggested that my fellow group mates and I try playing Sepak Takraw* with the local kids, learn how to weave rattan baskets with the elderly women, or accept a rusty machete to try opening a coconut when offered. There may or may not have been a little rice wine drinking in the mix, too – solely for research purposes, of course.

At first, my group mates saw this approach of observing and being overly curious as a bit uncomfortable at times, questioning the real purpose behind it. However, once we were back in wintery Copenhagen, writing our report, and I had developed the film photos I’d taken, the pieces started to fall into place.

The images that I had been casually taking throughout our stay – portraits, quiet corners, everyday moments – helped me to bring my ethnographic insights to life. I realised that these photos translated what I had observed and paid attention to in a way that could resonate with others, both in my team and beyond. All the details that ethnography can reveal – the juicy ones often hidden in plain sight – were made more tangible with photography and, as a result, more meaningful.

When research is complex, ethnography listens differently

Ethnographic research has taught me to pay attention to what quantitative data can overlook: power dynamics, worldviews, internal politics, and the unsaid. While we focused on measurable outcomes (soil acidity, water quality, biodiversity loss), I also tried to uncover some context to add texture:

For example, many plantation owners in the village wore matching GPS (Gabungan Parti Sarawak) political t-shirts and gold watches, mirroring the village leader’s style. This pattern wasn’t something people talked about explicitly. But when I showed photos, the visual cues sparked a conversation: What did those symbols represent? Who was aligning with whom?

These moments - how people used their space, the pride in someone’s face as they showed us their crops (or machete), the subtle power signifiers - might not have come through in a structured interview or a spreadsheet. But in a photo, they stood still long enough to be seen.

Ethnography is all about these messy, in-between layers of meaning, finding where they connect to create an understanding of people and their actions on their own terms, in their own contexts. Explaining this to someone trained to think in variables or control groups can be… well, not the easiest. Cue in why some anthropologists have used photography not just as a visual aid, but as a translation tool for ethnographic complexity.

What photography brings to ethnography

Photography has long been part of anthropology— although not always comfortably so. Colonial era anthropologists used the camera to categorise or exoticise with harmful consequences, and fieldwork photos were often dismissed as little more than holiday snapshots.

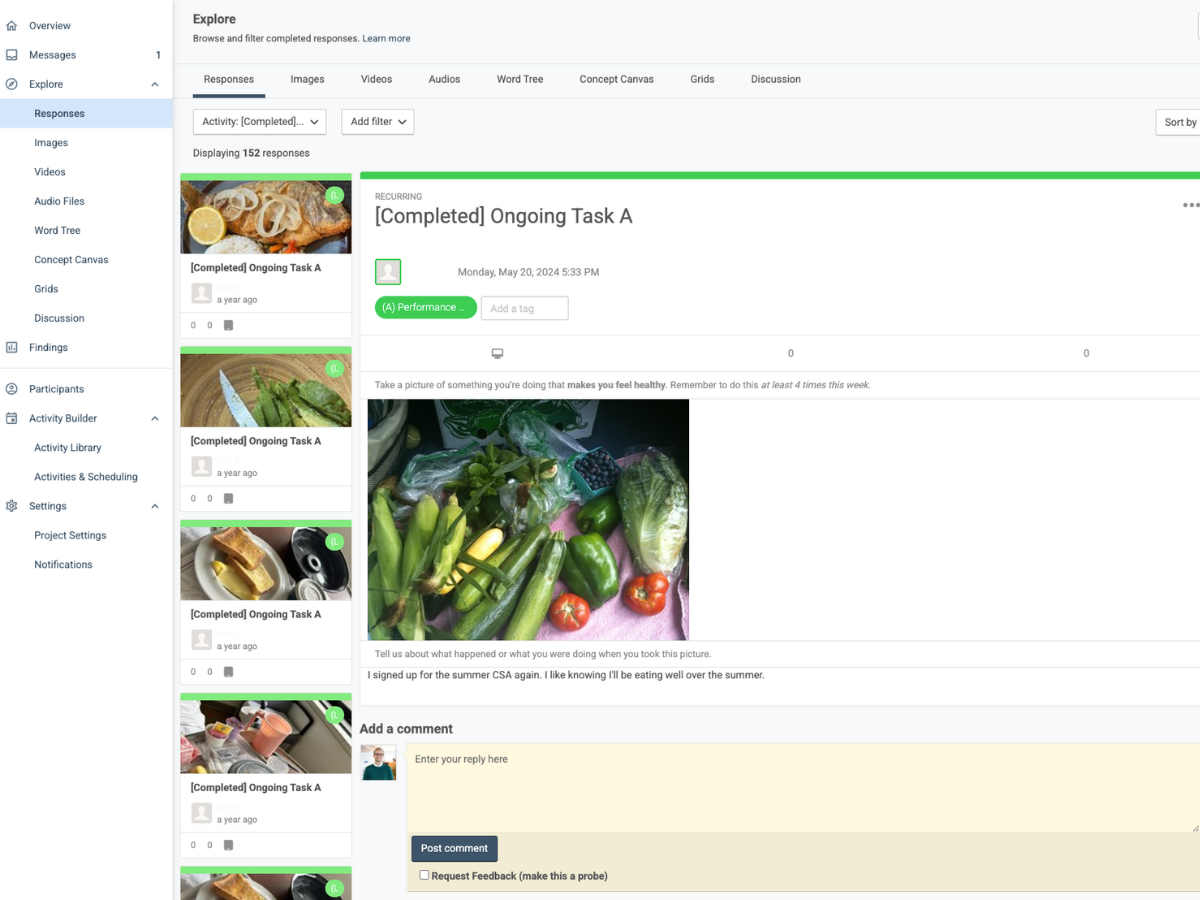

But by the 1980s, a more reflexive approach emerged, recognising that every photo is shaped by choice - what’s included, excluded, and how it’s framed. Back then, some researchers gave participants disposable cameras to document their own lives. Today, everyone has a camera in their pocket. At IIAB, we tap into this ubiquity through mobile ethnography - inviting participants to capture their own stories as a form of co-creation.

This more co-creative ethnographic photography can give a researcher access to the small, intimate moments of participants’ everyday life that can be quite hard to capture in a structured interview. In a recent project, participants were given prompts to respond to daily, creating visual “diary entries” through photos, videos, or screenshots. While my Borneo fieldwork offered the luxury of time and immersion, mobile ethnography allows for glimpses into intimate, everyday realities in a faster-paced research context.

In both settings, photography shifts the ethnographic gaze: from the researcher’s lens to a collaborative one.

Pausing to see the people behind data

In both my academic fieldwork and my time at IIAB, I’ve come to see photography as a way of pausing. It’s not just a way to document - it’s a way to notice. And sometimes, that pause opens up new ways of seeing those small but significant moments: how people used the space around their homes, the messages within the clothes they wore, and the pride in someone’s face when showing us their crops (or machete).

In the fast-paced world of business and strategy that demands insights immediately, it can feel like deep ethnographic fieldwork can seem like a luxury - too slow or costly to keep up with the pace of innovation. But what I’ve learned at IIAB is that speed does not have to compromise depth. Visual methods, such as mobile ethnography, allow us to achieve similar thoroughness in smaller moments, in a more scalable way.

In both academic and applied contexts, ethnographic photography helps recentre the human story. It builds empathy, adds texture, and makes complex social dynamics visible.

In a world that often demands quick answers, photography invites us to slow down - just enough to really see.

A note for future interns

Don’t be afraid to bring your academic tools to the nest. Whether it’s a theoretical framework, a fieldwork habit or creative methods like photography, IIAB is a place that values interdisciplinary perspectives. The work at IIAB goes beyond your typical user research, aiming to make the human behind it more visible in ways that inspire better questions, better conversations, and better solutions.

*Sepak Takraw is Malaysia’s national sport. It essentially involves playing volleyball with your feet, and it’s insanely difficult… You can imagine how good we were at it.

.png)

.png)